This lesson outlines the first step in dealing with the keyboard reconstruction question (ABRSM Grade 8 Music Theory).

Working with the Harmony

Look at the existing harmonic rhythm, then work out how often the harmony seems to change. The harmony should change often enough to sustain interest, but not so much that it becomes frantic and confusing. Usually this will mean changing the chord around twice per bar, although sometimes once per bar, or once per beat, will be appropriate.

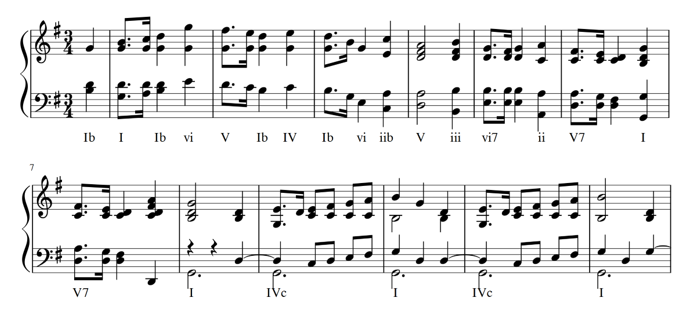

In this piano piece by Mendelssohn (Op.72 no.1), notice how frequently the harmony changes. At the most, it is on each beat of the bar. At the least, it is every bar. The harmony does not change on the quaver (eighth note) or semiquaver (16th note) subdivisions.

Look at the notes which fall on the beat (check the time signature to know how many beats per bar there are!) The notes which fall on the beat are the ones which should closely coincide with the harmony. Notes which fall between the beats are more likely to be dissonant with the harmony. It is important to have clear cut chords falling on the beat, in order to make the harmony coherent for the listener.

Choose chords so that:

- They fit the notes in the supplied material (but think about accented passing notes and appoggiaturas too).

- The harmony changes at least once a bar.

- The harmony is not anticipated (repeated from a weak beat to a stronger beat).

- The harmony is varied and not overly repetitive or motionless.

- The harmonic progressions are conventionally acceptable.

- Cadences are conventional [1].

- Modulations are conventional.

- The inversion of the chord is acceptable (look at the bass note/lowest note to determine the inversion).

Common Chord Progressions

In most cases it will be possible to work out a fairly traditional harmonic structure. We will expect to use the most common diatonic harmonies:

- I, ii, IV, V, vi, vii° in major keys (iii is only occasionally used).

- i, ii°, III, iv, V, VI, vii° and VII in minor keys. (III and VII are the tonic and dominant in the relative major key, and are derived from the melodic minor scale. III+ (augmented) is rarely used).

Primary Chords

Pieces of music usually begin with the primary chords (I, V and less often IV), to establish the key, and then more colourful chords are introduced for variety.

Towards the end of any phrase, we expect a cadence, which again will normally use primary chords (imperfect, plagal or perfect cadences).

Progression of 5ths

The most commonly seen progressions belong to the progression of 5ths. If you can fit the music to a part of the progression of 5ths, it will automatically sound logical. In the progression of 5ths, the chords move back to the tonic chord in steps of a 5th.

The most commonly used section of this progression is VI-II-V-I. ii7 is also normally followed by V, or Ic (see below). The major supertonic 7th (II7) works in the same way.

Decoration

When working out the likely harmony, the melody note which sounds simultaneously with the bass note may or may not be part of the chord.

When the melody note is NOT a triad note, it will be a suspension, appoggiatura or accented passing note (they work in much the same way), or it will belong to an added chord (e.g. V9) or chromatic chord (e.g. Neapolitan 6th).

A suspension/appoggiatura/accented passing note will fall by step to the next note, which WILL be a chord note.

In the following example, which chords would make a good progression?

The minim (half note) suggests we have come to the end of a phrase (longer note value), and as the key is C major, we would expect a perfect cadence (V-I) here.

The most commonly used chord before V at a cadence is ii. Do these chords fit with these two beats?

At first glance, you might say no, since E is not in the chord of D minor (ii), and C is not in G major (V). However, you can treat both the E and C as accented decoration notes.

The D fits with D minor (ii), and the B with G major (V), making a good progression. You could write this in the left hand:

Instead of asking yourself “which triads fit this note?”, turn the question around to “can I make this note fit a common harmonic progression?”

Chromatic Chords

Most Question 2s include at least one chromatic chord. This may be one of the more common “named” chromatic chords, such as the Neapolitan 6th or German 6th, or it may be simply an altered triad or 7th chord.

With all chromatic chords, the easiest way to progress to the next chord will generally be by small movements, orrepetition where movement is not possible.

Move by semitone steps, repeat notes which are common to both chords, and use small leaps only if necessary. For example, iv moves smoothly to V7:

Two notes move by a semitone step, one note is common to both chords (F), and the other movement is a third

In this extract from Mozart’s 6th piano sonata, which chord would fit in the first blank bar? (The prevailing key is D major). Try to work it out for yourself first, then read on!

The bass clef stave gives us the chord notes Bb-D-F. These make up a Bb major chord which is ♭VI in the key of D major, so ♭VI would work. Alternatively, we could add G# into the mix, making the German 6th chord. Mozart in fact, uses the German 6th here. This is what he wrote:

Modulations

Modulations are normally (but not always) brought about by the use of V(7)-I in the new key, most often preceded by a pivot chord (a chord which exists in both keys).

However, also remember that other variations are also relatively common:

- V7 moving to a chord which is not I (e.g. VI, vii° etc.)

- No pivot chord used.

- Moving directly in the new key without V7.

The diminished 7th chord is also a powerful modulation tool. There are only three different diminished 7th chords (if you spell them enharmonically):

- C-Eb-Gb-Bbb

- C#-E-G-Bb

- D-F-Ab-Cb

The diminished 7th chord starting on D# is enharmonically the same as no.1 here, which contains Eb, (D#-F#-A-C is the enharmonic spelling), and so on. So, you can easily move in quite unexpected directions, by re-spelling a diminished 7th.

For example, in the key of C major a typical chord progression could be I – vii°b7 (Bdim7) (B-D-F-Ab). The Bdim7 chord could be re-spelled as Ddim7 (D-F-Ab-Cb) which is vii°b7 in Eb major.

This would allow a quick, but smooth modulation to the relatively distant key of Eb major (or minor).

Notice that the natural resolution of the diminished 7th chord creates a chord with a doubled third.

[1] By “conventional” I mean “done in the normal way” according to the traditions of Romantic era harmony.