How to Write Programme Notes for Music Exams

This article aims to give you some practical, actionable advice on writing programme notes for a music exam.

In a nutshell, the main steps are:

- Know who your reader is (clue: it’s not the examiner!)

- Gather information from sources of authority, covering the musical and historical background to the pieces in your programme (details below). Keep a detailed record of the sources you use.

- Read the style guide (summarised below), especially with reference to correct formatting of titles.

- Write your notes, and carry out further research if necessary. Make a note of potential viva voce questions.

- Proofread for grammar, spelling and check the presentation. Then ask someone else to do the same.

(Note for US readers, the UK spelling is “programme”, US is “program”)

I strongly recommend that you download a copy of the ABRSM’s DipABRSM document “Writing Programme Notes – a Guide for Diploma Candidates”. https://gb.abrsm.org/media/57042/writingprognotesapr05.pdf. Although the DipABRSM is being withdrawn, this PDF is still very useful.

You can download a PDF version of these notes here: https://shop.mymusictheory.com/b/Qe57Y

Always check the specific requirements of the exam board you are using, by reading the most up to date syllabus. In particular, pay attention to the required word count.

Overview

The first page of your programme notes will be your title page.

The title page should normally contain:

- The full title of the exam and name of instrument

- The date of the exam

- The word count

- The works in your programme, in performance order

You will then discuss each piece in your programme in turn. Include a heading for each, giving the full title of the work, and the composer’s name and dates.

Voice candidates need to include the text of each song. For non-English language songs, a translation (cited) should be provided in the facing column.

Number the pages.

Who are you writing your programme notes for?

A common misconception is that programme notes exist so that you can prove to the examiner that you have analysed the music in great depth. Not so!

You are not writing for the examiner.

So, who exactly are you writing for?

You are writing for a “typical concert-goer”, or non-expert. The examiner’s job is (among other things) to judge whether you have successfully done this.

It can really help to think of a real person that you know, and write your notes as though you were going to tell that person about your repertoire. Paste a photo of them in your notebook while you’re researching, to help you stay focused. Constantly ask yourself questions like “Would [Marjory] understand this?”, “Would [Xavier] be interested to know that?”, “Will this send [Vladislav] to sleep?”

Your notes should be

- interesting

- relevant

- error free

The following is an example of what not to do:

“The first measure for the right hand consists of chord tones of the E major triad with two passing notes in the following manner: After the up-beat B, the E major triad follows, starting with G#, A as passing note; chord tone B, chord tones E, E, E, F# as passing tone, E. Then follows the exact repetition of the first half of the measure”.

[Geiseking, Walter; Piano Technique (referring to the Allemande of the French Suite in E major by J.S. Bach]

This is too dry, too analytical and too technical. It doesn’t enhance the reader’s enjoyment of what they are about to hear. While it’s important that you know how the music is constructed, in great detail, the average concert-goer is looking for something a bit more enlightening in their programme notes.

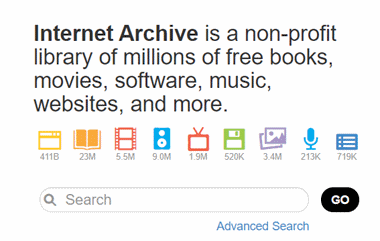

Here are some rather more readable notes (source: www.archive.org):

“Bruch’s first sketches for his Violin Concerto in G Minor, Op. 26, date from 1857, but the work was not finished and premiered until 1866. Within the context of virtuosic, violinistic writing, the Concerto also reflects Bruch’s vocal heritage, particularly in the recitative-like dialogue of the introductory first movement, in the supremely lyrical second movement, and in the dramatic second subject of the last movement.”

[Programme notes from CBS Masterworks recording of Bruch’s Violin Concerto, written by Philip Ramey, accessed from archive.org]

“The year 1796 was a watershed in the history of the trumpet. It was in that year that the Viennese instrument-maker Anton Weidinger perfected a key system that released the trumpet from being restricted to the key in which it was built; i.e. the key, usually C or D, dictated by the length of the tube. […] Franz Joseph Haydn was greatly impressed by its possibilities and immediately wrote his Trumpet Concerto […] within about 20 seconds of the soloist’s entry, the trumpet plays a downward chromatic scale which must have sounded impossible!”

[Programme notes from EMI Classics recording of Haydn’s Trumpet Concert in in Eb, Hob.:VIIe/1 , by Robert Dearling, accessed from www.archive.org]

Incidentally, www.archive.org is probably the best source on the internet for browsing “real” programme notes. It’s a great place to start your research, and also to get an idea of what sort of writing style you are expected to use.

- When you arrive at the website, type in the name of the piece into the archive.org search box (not into the Wayback Machine search box at the top of the page).

- Use the rightmost scroll bar to pull the page right down, until you see a list called “download options” files on the right of the screen. Select “PDF” as this will open up a scan of the sleeve notes to the recording.

- Don’t forget to listen to the recordings too. This will widen your experience of other people’s performances.

Your programme notes need to show the examiner that you understand the

- Historical background to your pieces

- Musical structure of your pieces

If your exam includes a viva voce the examiner will use your programme notes as a springboard for further discussion, so you should be prepared to discuss in depth any point which you include in your notes.

Make a “Viva Voce” section in your notebook: Draw a picture of your imagined examiner at the top. On this page keep a list of questions that they might potentially ask you, based on what you’ve written in your submitted notes.

For example, if you mention that the clarinet which the piece was written for had only 13 keys, you might jot down potential viva questions such as “Who invented those keys, where and when?” “Which notes did they make possible?” “Which keys were added next?” “How many keys does a modern clarinet have?” And so on.

Practise answering those questions by talking out loud to the picture of the examiner that you drew. (It might help to remember the journalistic keywords; What, where, when, who, why and how.)

Is it OK to copy?

No! Not even a little bit.

It should go without saying that your notes must be your own work. Do not be tempted to copy from the research sources you find. You will need to sign a declaration that the notes were not copied, and you are likely to be disqualified from the exam if you plagiarise.

Of course, some sentences, such as “Beethoven died in 1827”, are universal and not “owned” by anyone. Use common sense.

Research – What to find out

One problem that many diploma candidates come up against is that “you don’t know what you don’t know”. How you can know what you are supposed to find out about each work in your programme?

I’ve already mentioned searching archive.org for existing programme notes. Another obvious source of informational nuggets is, of course, your teacher, if you have one. In addition, you need to read plenty of books (not just pages on the internet).

What do you need to find out?

Broadly speaking, you should find out as much as you can about

- the instrument (or voice) you play, and its technical development at the time of composition

- the structure of and background to the music you are playing, including why it was composed

- the biography of the composer of the work

- the stylistics of the era it was composed in

- the wider socio-political background of the era

- the most important performers of the work, particularly at its premiere

While you are doing this more general type of research, you may well come across some very interesting nuggets of information relating to your specific pieces. Always be on the look out for “extra-special” facts that you can include, as these can make your programme notes sparkle.

Keep a careful note of all the sources you use. Write down the title, author, date and publisher. If you use direct quotations, make a note of the page number for future reference.

What to Read – Who to trust

You need to research your pieces using only trustworthy sources, and then write your notes using your own words.

Wikipedia is not an authority – Beware!

- Wikipedia is open to edit by anyone. There is no guarantee at all that any information on the website is correct. It is not a credible source and must not form the sole basis of your research.

- However, it can be a useful starting place. It may give you ideas for further research, and at the end of the page there is often a reading list.

- Double check any information you find on Wikipedia. Do not use any information which you have not checked with an alternative credible source.

Trustworthy sources include:

- Published books (but not most self-published books)

- Check who the publisher is. Books published by Amazon, Createspace, or Lulu are self-published. If you have not heard of the publisher, find out whether it is a self-publishing company or not.

- If you find a self-published book and are sure you can trust its authority, then it is possible it will be fine. Use your judgment.

- Many older books (pre-1950s) are written in a descriptive/poetic style, rather than a factual/objective style. Select more modern books if possible.

- It is unlikely (but possible) there will be a book “about” the piece you are playing. You could look for books specifically about:

- the composer

- the era (e.g. “Romantic”)

- the genre (e.g. “chamber music”)

- the instrument (e.g. “the trombone”)

- the family of instruments (e.g. “woodwind instruments”)

- performers or conductors (e.g. “Daniel Barenboim”)

- Existing programme notes

- These can be found inside CD/record covers, concert programmes (many available online), and recital programmes (check accuracy especially if they are “junior” recitals).

- Check www.archive.org.

- Read the preface of the printed score. For duos, the piano part will often include an introduction with useful information. Scores by different publishers (and therefore with different prefaces) may be available on archive.org .

- Dissertations. Many master’s degree and doctoral dissertations can be found online or in some libraries.

- Use scholar.google.co.uk/ to search online. Also try academia.edu.

- While these can be very useful documents, there is no guarantee that they are without error, so double check what you find.

- Dissertations are often useful because they contain relevant bibliographies which can point you towards a useful reading list.

- Grove Dictionary of Music

- Available online at oxfordmusiconline.com. You will need a paid subscription for home use, but check your local library – it may offer access. ISM members have access included with their subscriptions. Find out if your teacher is in the ISM and ask them nicely to print some articles for you.

- Periodicals and newspapers

- Some are available online, or try your library.

- Useful for reading about the premieres of pieces, and public reaction.

- Academic websites

- In the UK, academic institutions have the domain suffix ‘.ac’. In the USA it is ‘.edu’.

- Publishers

- The ABRSM suggests, particularly for contemporary works, that contacting the publisher directly for information may be useful.

- Other websites

- Composer-specific websites which are run by living composers or their descendants or by other societies, are often good sources. For example, rvwsociety.com/ is run by the Vaughan Williams Society.

- The British Library book search website explore.bl.uk/ can help you find relevant literature.

- abebooks.co.uk is a great source of cheaper second-hand academic books.

- Orchestras/musical groups sometimes run informative websites. The New York Philharmonic archives can be found at nyphil.org/ for example. This is a useful source to read about first performances or to find programme notes.

- archive.org is a treasure trove. You may find out-of-copyright books, magazine articles, or record-sleeve programme notes, for example.

- Performers’ personal websites can sometimes be useful.

- Other websites may be useful – use your discretion. Ask yourself, “who wrote this, and can I trust them?”

You need to know the developmental history of your instrument. If you have no idea where to start, the Yehudi Menuhin Music Guides might be a useful place. There are 16 books, each covering one topic (including voice). See on Amazon here: amzn.to/38QfXko

These books should also give you clues about some of the composers, works, and past performers which may be relevant to your topic.

The Open University runs a free course on music research:

https://www.open.edu/openlearn/history-the-arts/an-introduction-music-research/

Some Questions to Get Started

To help you structure your research, I’ve listed below a long series of questions.

For each work/movement of a work in your programme, try to answer as many questions as you can.

Then write your programme notes based on what you’ve found out.

- Remember: Your programme notes must not be copied word-for-word from anywhere. You may be disqualified if you are found to have copied someone else’s work. Direct quotations can be used, but you must credit the author. (It is not necessary to name the publication).

You will need to research first, and then decide which of the information you discover is interesting/relevant enough to include in your notes. You may find that once you begin writing your programme notes, more questions come to you which are specific to your case, and you will need to return to the research stage.

Try to discover the following. (Some questions may be irrelevant, and some answers may be impossible to find. The questions are in the past tense because there are more deceased composers than living ones: alter accordingly.)

Music Research Questions

Full name of composer?

Year of birth and death?

Cause of death?

Nationality/Country?

Did they ever live abroad? Where?

Who did they work for (if anyone)? Where?

Did they play the instrument this piece is written for?

What other instrument(s) did they play?

Were they particularly prolific? If so, how?

Are they famous for inventing or pioneering anything?

What genres did they write in, and which are their “main genres”?

Name a few of their most famous pieces.

Did they write any other pieces for the same instrument(s)? Name some.

Did they have any famous relatives?

Did they have any long-lasting musical partnerships?

Are there any noteworthy events in their life?

What are you favourite other pieces by this composer?

Listen to three of their pieces which you’ve never heard before and write the names here. How do they compare to the work in your programme?

What year was the piece in your programme written?

Did anything of historical importance happen that year? (Was it before or after?)

What country was it written in? Is that the composer’s home country, or somewhere else?

Was it a time of peace/war/revolution/disaster?

What is the name of the musical era (e.g. Baroque, Classical etc.)?

What are the defining stylistic elements of this era?

Which other composers lived at this time, and how do their styles compare?

Was the composer involved in politics, or in any revolutions of musical/artistic style?

Was the composer ahead of his/her time, or conservative in style?

Which other composers or styles influenced this composer?

Can you find any pieces by other composers that are similar to this one?

Did the composer have any rivals/detractors?

Why was the piece written? (for an event, for a competition, for a patron or perhaps a combination of these?)

Was it composed for a particular performer? If so, what was the relationship between the composer and performer?

Was it dedicated to anyone? What was their relationship?

Who performed it first and where (which country, which theatre)?

What was the public’s reaction to the premiere? Why?

What other similar pieces did the composer write?

Is the piece typical or atypical for the composer? Why?

What key is the piece in?

Does it modulate? To where? What relationship are these keys (e.g. relative minor, dominant, etc.)?

What is the tempo and does the tempo change? How?

What form (e.g. sonata, rondo) is it in? (Is it unconventional at all?)

How many separate thematic ideas are there?

How do they contrast with each other?

How are they linked together?

How are the main themes built? (Are they based on arpeggios, scales, a particular interval, etc.?)

Where is the climax (most exciting/tense point)? Can you describe it in words?

Think of some adjectives to describe this piece.

Does the piece go to any extremes (e.g. of range, dynamics, tempo, etc.)?

Does this piece require any special techniques (e.g. half-pedalling, pizzicato, flutter-tonguing, etc.)?

What are the most interesting/unusual things about it (e.g. the melody line, the rhythms, the virtuosity, etc.)?

What was the developmental stage of your instrument at the time this was written?

Are there any big differences between a period instrument and your modern instrument?

Who had made the most recent mechanical improvement to the instrument at the time the piece was written?

Do you think playing the piece on a modern instrument poses problems, or makes life easier? Why?

Does the piece make good idiomatic use of your instrument’s capabilities (range, dynamics, articulations etc.)?

Multi-movement works

How many movements are there in the work, and how many will you perform?

If you are not performing the whole work, why did you pick these particular movements?

What are the main contrasts between the movements (e.g. tonality, register, mood, etc.)?

Vocal Music

What language is it in?

Is that the composer’s mother tongue? If not, why was it written in that language?

Who made the translation?

Is the song taken from a composite work, e.g. an opera or mass?

Is it religious or secular?

If religious, what was the composer’s relationship with that religion?

What is the song about?

What (if any) is the name of the character who is singing?

Is there any background information regarding the story which the listener should know?

Do the words suit or contradict the mood of the music?

Are there any examples of word-painting?

Writing Style

Write in a friendly but formal style.

Choose information which is relevant, interesting and balanced. Write approximately the same amount for each work in your programme, perhaps with longer notes for longer pieces. Discuss different aspects of the work – biographical, historical and analytical. Don’t limit yourself to one angle.

Avoid specialist music theory jargon. Terms like “secondary dominant” or “German 6th” are not widely understood by the general public. Consider carefully whether it’s relevant to include at all: if it is, then be sure to explain what the term actually means.

The ABRSM says your writing should be “persuasive” – in other words, you need to write with confidence in your knowledge, and clarity in your message.

Use grammatically correct English. If English is not your first language, you may wish to take advice from someone who can check your grammar and spelling.

Do not use contractions (write “that is” and not “that’s”).

Take care over the presentation of your work (be consistent with text size, headings, spacing etc.).

Style Guide for Programme Notes

Below is a summary of how to use correct capitalisation, italics and quotation marks. If you are in any doubt, check the Grove dictionary for clarification. Another comprehensive reference book is Music in Words by Trevor Herbert, published by the ABRSM.

(For “title case” see titlecase.com/ for help. “Local title case” means you should use the title case standard in the language of the text – check Grove for clarification).

| Type of Text | Style | Example |

| Adjectives formed from proper nouns | Capitalise | Schubertian German |

| Dynamics | Normal capitalisation, italics | mp fortissimo |

| Foreign terms common in English | Normal styling | allegro legato |

| Foreign terms not common in English | Normal capitalisation, italics | giocoso saltando |

| Notes | Capitalise, accidentals to right | B C# |

| Periods | Capitalised | Renaissance Romantic |

| Quotations | Double quotation marks | Fieldorgsky claimed his Nocturne was “too hard for amateurs”. |

| Tempo (not used as a title) | Normal capitalisation | allegro moderato |

| Titles | ||

| Ballets | Title case, italics | The Nutcracker The Rite of Spring |

| Books | Title case, italics | An Outline History of European Music The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians |

| Instrumental works: descriptive titles | Title case or local title case, italics | Symphonie fantastique A Gloucestershire Rhapsody |

| Instrumental works: genre-based titles | Title case | Intermezzo in A Concerto in Eb |

| Instrumental works: nicknames (not original names) | Title case or local title case, single quotation marks | ‘The Moonlight Sonata’ ‘Eine kleine Nacht-Musik’ |

| Movements | Title case | Allegro Moderato Allegro con Brio |

| Opus numbers | Lower case, comma separates opus and number | op.118 op.118, no.2 |

| Vocal works: genre-based titles, mass acclamations | Title case | Mass in B Minor Agnus Dei |

| Vocal works: composite (operas, song cycles, religious works etc. with descriptive titles) | Title case, italics | La Bohème Dido and Aeneas Das Lied von der Erde Christmas Oratorio |

| Vocal works: arias, choruses, recitatives, psalms, hymns | Capitalise first word only (and all nouns in German), single quotation marks, (note lower case after exclamation mark) | ‘Hark! the echoing air’ (English) ‘Ah! mon fils, sois béni’ (French) ‘Auf dem Wasser zu singen’ (German) ‘Misero! io vengo meno’ (Italian) |

| Vocal works: songs (non-sentences) | English: use title case Foreign: check individual songs | ‘Song to the Seals’ (English) ‘Le Temps des Lilas’ (French) ‘Chanson triste’ (French) |

| Vocal works: songs (sentences) | Capitalise first word only (and all nouns in German), single quotation marks | ‘Why do I love?’ (English) ‘Du bist wie eine Blume’ (German) |

Organising Your Words

Try to link your facts together logically. Look through your research notes and try to make your own conclusions, links and comparisons, based on what you have found out.

The most typical ordering of paragraphs is (1) biographical info, (2) background info and (3) musical info. If you have a good reason to change this order, that’s fine, as long as it’s a good reason.

Have one main idea per paragraph. Use a “topic sentence” to start the paragraph (a sentence which is the main point of the paragraph). The rest of the paragraph should add more detail, explanation or description to the topic sentence. E.g.:

Himpledimp’s Rondo in F Flat is somewhat unconventional in character. The usual rondo pattern employs a main theme which is interwoven with a series of contrasting episodes in the same overall style. Himpledimp, however, punctuates each theme with a musical episode which is completely unconnected stylistically to the opening thematic material. The first episode is a parody of the Russian National Anthem, the second is a quodlibet (two melodies combined) of the theme tunes to “Eastenders” and “University Challenge”, and the third is a pastiche based on J. S. Bach.

Keep it objective. Don’t write personal views such as “I love this piece because….” Instead, find out what the opinion of others has been (the public at its premiere, the composer him/herself, the criticism in the press, the reactions of other composers, etc.).

Chopinsky wrote in his biography that he greatly disliked the piece on hearing its premiere in the Albert Stadium, but the audience’s appreciation was shown by the 392 standing ovations the performance received – a record number in the Stadium’s history.

It is better to write a small number of paragraphs – each one focused and structured logically, with links bridged between them – than to write a large list of disconnected “factoids” with no conclusions of your own.

Good luck!